Food in Camp - A Reflection

Food in Camp

By Camille Daw, Fellow, Friends of Minidoka

Reflecting on the food served at Minidoka, incarcerees did not have choice in their diet. The meals remained rationed and had little nutritional value in the first couple of months. Incarcerees and WRA staff recounted the awful meals they ate; lest they starve. Arthur Kleinkopf, the superintendent of education at Minidoka regularly recorded his meals and portions while working at Minidoka. One of his less favorite meals consisted of fish, especially with curry. In one diary entry, he wrote: “See people going to the dining hall door, pause a moment, and then turn and leave. It's fish.” Despite many Japanese dishes containing fish, the seafood at Minidoka remained unfavorable, primarily because the WRA did not provide fresh fish, and the meal was often mixed with curry powder.

One of the challenges of food at Minidoka was related to the lack of control that incarcerees had over their own eating habits and mealtimes. Incarcerees were required to eat at the set mealtimes, often with a short time to eat, and crowded into a mess hall with many strangers. Instead of eating meals with their parents, children often ate with their friends, significantly breaking up the family dynamic.

However, after the first year, many fresher and more culturally oriented foods appeared in mess halls as incarcerees raised fresh vegetables and animals in Minidoka’s agricultural areas. Some of the food raised at the camp included pigs, chickens, beans, alfalfa, gobo, onions, potatoes, carrots, tomatoes, corn, cabbage, daikon radishes, napa cabbage, green peppers, beets, eggplants, celery, spinach, and melon fruits, according to a report on the first year of agriculture at Minidoka. The Minidoka Interlude, the camp album, also mentions a tofu factory, where incarcerees made their own tofu.

As the quality of food increased, especially with the availability of fresh produce and meat, the taste depended on the head cook of each mess hall. However, as explained by Jim Oyama, sometimes the way the food turned out was beyond the cook’s control. For example, in an Idaho Statesman article, he stated that the first time he cooked rice, the elevation caused the rice to turn out only half-cooked. He had to finish it by steaming the rice in an oven. Jim also had to learn how to cook beef heart, which, according to him, they “got back more than they served.”

Not only were Minidoka’s cooks in charge of feeding hundreds of people daily, often with subpar at best ingredients, but they also had a very small space and time to cook the food. In the picture below, of Jim Shiga, one of Minidoka’s better cooks, according to Densho, the photographer includes a view of the Minidoka kitchen. Along with tight spaces, the Idaho heat made cooking a very unfortunate job in the summer. The lack of ventilation in the mess halls, combined with the hot stoves and Idaho sun led to fewer “hot” meals in the summertime. Though in the winter, the mess halls provided warmth from the hot ovens and stoves, along with the sheer amount of people crammed into the small space.

(Image: Jim Shiga, well-known for his cooking skills, prepares a meal in the camp's warehouse kitchen, Courtesy of the Mitsuoka Family Collection, Circa 1944).

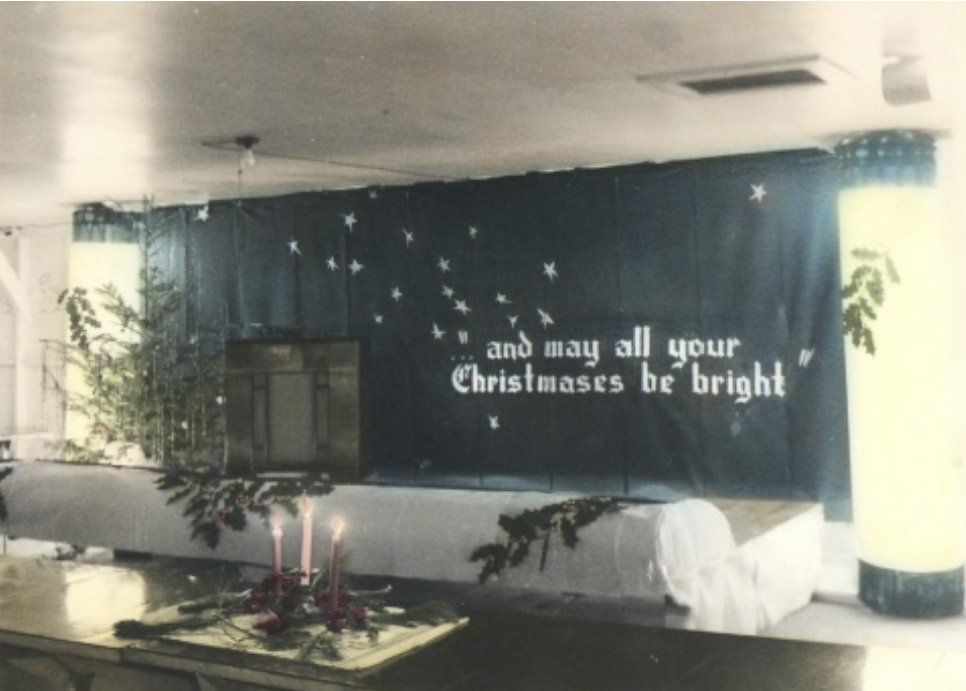

Around Christmas, mess hall decorating contests were held. Each block decorated its space with paper, candles, and plants. Often incarcerees found materials for their decorations around the camp. For example, sagebrush frequently appeared as a Christmas tree. While the decorations seemed very merry, the food was a much different story. In 1942, two boys are pictured, eating their Christmas dinner at Minidoka. Their meal consisted of sausages.

(Image: Block 28 Mess Hall, Winner of the 1st Prize Decorating Contest, Courtesy of the Kinoshita Family Collection, 1942)