Youth Hi-Lite: Community Divided — Draft Resisters and the JACL

By Ronan Byrne, Friends of Minidoka Undergraduate Summer Intern from College of Idaho

The incarceration of Japanese Americans during the second World War was an experience that transformed the social fabric of America’s nikkei community. The collective effects of the ordeal were felt profoundly, and would last long after the conclusion of the war. Beyond the obvious harm of being taken from their homes and businesses, camp survivors faced community divisions and ideological challenges as they were forced to reckon with their new position as “enemy aliens,” after the US Army reclassified Japanese Americans as 4-C. Different parts of the Japanese American community had distinct reactions to their treatment by the federal government. These differences in philosophy could lead to harsh tensions. In particular, bitter divides were drawn around the question of whether to resist or cooperate with the government’s actions.

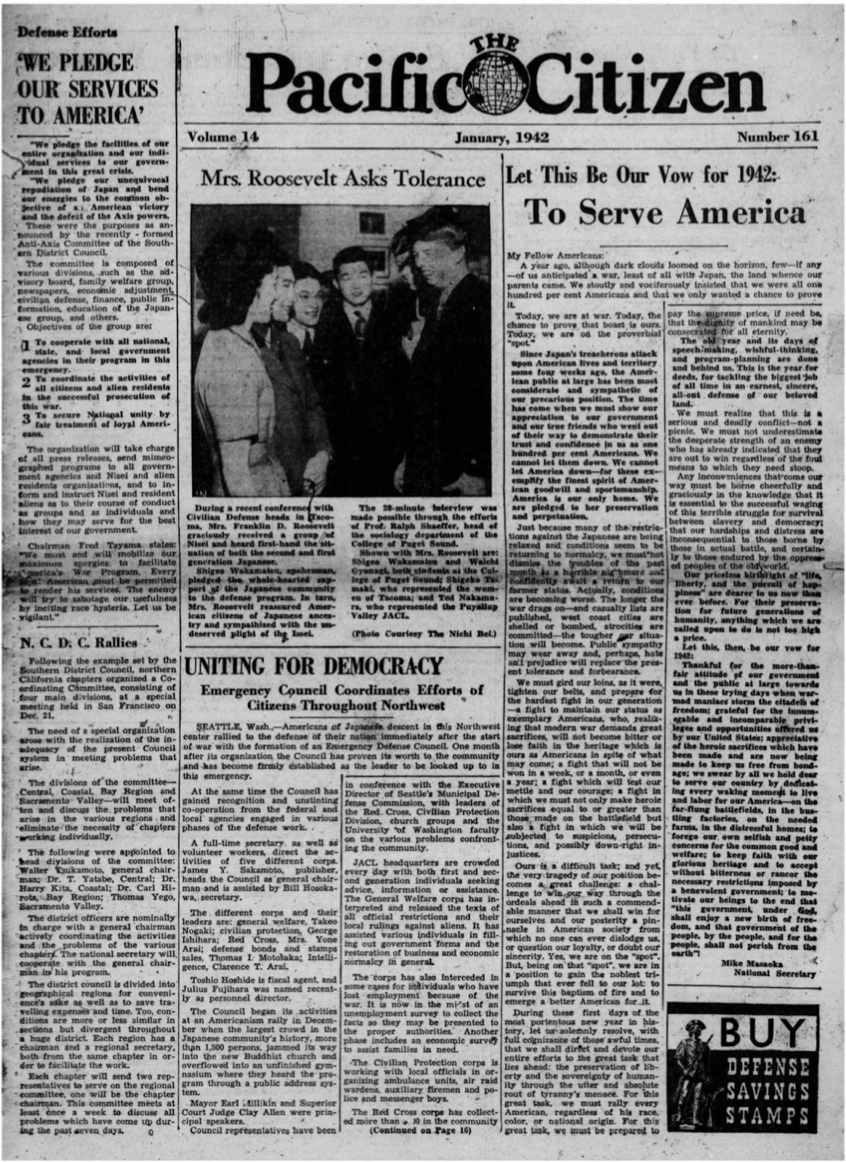

The Japanese American Citizenship League (JACL) felt that the best response to internment was to prove their loyalty through cooperation. They took a pro-government and patriotic military stance during the war, encouraging cooperation with the War Relocation Authority. One of the JACL’s main avenues for expressing their position was their official newspaper, the Pacific Citizen. In January 1942, the Pacific Citizen published a statement which laid out the JACL’s position in unequivocal terms (see below). The article was penned by Mike Masaoka, the JACL’s national secretary and a leading advocate for Japanese American cooperation with the US government. In the text, Masaoka acknowledges that discrimination and mistrust may be worsening for Japanese Americans. Determined to face wartime prejudice by doubling down and showing loyalty as “one hundred percent Americans,” he expresses appreciation for the US government, and states that any “inconveniences” must be “borne cheerfully and graciously.” Furthermore, he vows on behalf of the Japanese American community to work and fight for the American war effort as a way of establishing loyalty and gratitude.

While the JACL encouraged Japanese Americans to go along with incarceration and military initiatives, some of those incarcerated had different ideas of how to respond. There were various forms of resistance throughout the ten camps, with equally diverse ideological foundations. One way that incarcerees stood up for their rights was through draft resistance. For much of the war, young Nisei men had been ineligible for the draft and classified as “enemy aliens” despite their status as citizens. When the draft was reinstituted, some took objection to the injustice of being ordered to fight for a government that had placed them and their families behind barbed wire in a concentration camp. Some of the concentration camps had organized movements. In others, including Minidoka, resistance was an individual decision. All told, nearly three hundred individuals from eight camps refused to report for the draft, on the basis that they should not be expected to serve the country while they were not being given the rights of citizens.

Unsurprisingly, this difference in philosophies led to tension and conflict between those who advocated for cooperation and those who resisted. Resisting the draft was an unequivocal step away from the JACL’s prescribed course of action. In response to their act of protest, draft resisters were publicly condemned by newspapers and spokespeople. The Pacific Citizen, as the JACL’s primary way of communicating with their members, took a particular stake in the issue. One editorial from April of 1944 (see below), titled “The Bitter Harvest,” explains that “By their action these young men, and those who prompted their action, have injured the cause of loyal Japanese Americans everywhere.”

Interestingly, this article takes a more sympathetic approach than other pieces created by the JACL and its supporters. While many articles attack the character and loyalty of the draft resisters, in an apparent effort to separate them from the rest of the community, “The Bitter Harvest” takes the time to consider the circumstances that these young men were faced with. It acknowledges the hardships of incarceration, and how that influenced their willingness to serve a government that mistreated them. Ultimately, while it recognizes the draft resistors' point of view to a limited extent, the article still concludes that resistance threatens the image of the Japanese American community, and condemns it as an expression of disloyalty. This editorial, more clearly than others articles published by the Pacific Citizen, expresses the JACL’s attempts to distance draft resisters from the rest of the community out of the fear that they would tarnish the reputation and image of “loyal” Japanese American citizens.

Unfortunately, the rhetoric espoused by the JACL had tangible consequences. Draft resister Mits Koshiyama, from the Heart Mountain concentration camp, gave an interview in 2001 in which he detailed some of the hardships faced by draft resisters at the hands of their own community in the wake of the war. He discusses anti-draft resister sentiments among Japanese American populations and the family members of resisters being harassed both during and after World War II. He shared the story of an acquaintance who was singled out at a meeting by a former friend and told that he did not deserve to live in America because of his resistance. Tensions were high in the aftermath of World War II and incarceration. Veterans and the families of veterans experienced a different war than the draft resisters, though both experienced the same tensions and pressures of World War II. Many Japanese Americans shared the sentiments of the JACL and were afraid of drawing attention to themselves for fear of continued discrimination, hatred, and prejudice. There was a sense that, by showing “disloyalty” to America and the war effort, draft resisters had tarnished the status of the community as a whole, and undermined the efforts of the JACL and their allies to prove themselves as loyal citizens.

Draft resisters endured years of marginalization and discrimination as the community recovered from the major wartime upheaval. It was not until decades later, in the wake of the redress movement and other cultural shifts, that the JACL began to reconsider its position. The organization’s actions toward the draft resisters began to be called into question with the Lim Report, a 1989 investigation into the JACL’s wartime conduct. In 1990, a resolution was proposed to recognize the courage of the draft resisters. In 2002, the JACL formally apologized for its actions and again issued a public recognition. The conciliatory efforts were met with mixed reactions from veterans and resisters alike; the wounds of incarceration had left deep divisions in the community, which even decades later had yet to fully heal.

Works Cited

Koshiyama, Mits. “Mits Koshiyama Interview Segment 19.” Interview courtesy of Densho. July 14, 2001, https://ddr.densho.org/interviews/ddr-densho-1000-130-19/

Lyon, Cherstin. “JACL Apology to Draft Resisters. Densho Encyclopedia. 11 June 2024. https://encyclopedia.densho.org/JACL%20apology%20to%20draft%20resisters

Masaoka, Mike. “Let This Be Our Vow for 1942: To Serve America.” Pacific Citizen, January 1942.

“The Bitter Harvest.” Pacific Citizen, 25 March 1944.