Japanese American Incarceration during World War II

"... these people are living in the midst of a desert where they see nothing except tar paper covered barracks, sagebrush, and rocks. No flowers, no trees, no shrubs, no grass. The impact of emotional disturbance as a result of the evacuation . . . plus this dull, dreary existence in a desert region surely must give these people a feeling of helplessness, hopelessness, and despair which we on the outside do not and will never fully understand."

- Arthur Kleinkopf, Superintendent of Education, Minidoka Relocation Center, from Relocation Center Diary

About 18 miles northeast of Twin Falls, stands a lone lava rock chimney tower and portions of a building wall; these building remnants are the most conspicuous remains of the “Minidoka War Relocation Center”; a WWII American concentration camp where almost 14,000 people of Japanese ancestry were incarcerated between 1942 and 1945. These American "sites of shame" are a stark and solemn reminder of a disturbing chapter in American history.

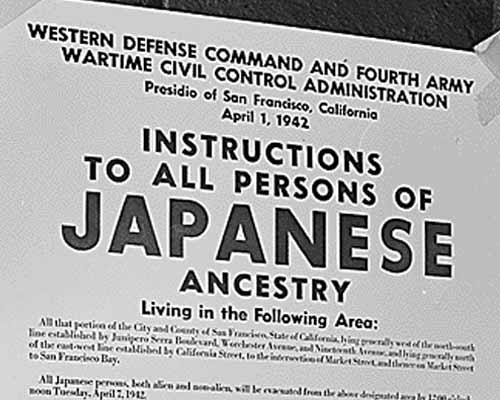

Executive Order 9066

Following Imperial Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, a combination of wartime fear, hysteria, and longstanding racism against Japanese Americans put pressure on politicians to enact restrictive legislation. In February 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which ordered the initial forced removal of 112,000 Japanese Americans from the West Coast. Justified in the name of military necessity, all West Coast residents of Japanese ancestry, also referred to as Nikkei, were forced to leave their homes, neighborhoods, businesses, farms, and schools and report to incarceration camps in the single largest forced relocation in U.S. history.

Over two-thirds of the Nikkei incarcerated were American citizens yet few Americans raised their voices in protest of the removal order. The system of checks and balances that is supposed to protect the rights and freedoms of American citizens was trampled upon in what legal scholars have described as one of the worst violations of constitutional rights in American history. By the time the last incarcerees were released and the camps de-commissioned in 1946, the Japanese Americans had lost homes and businesses estimated to be worth, in 1999 values, 4 to 5 billion dollars.

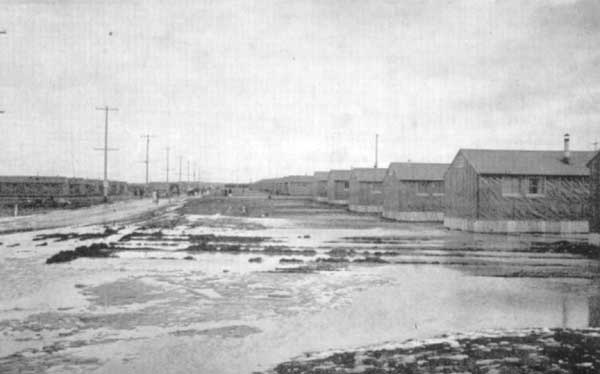

The Minidoka War Relocation Center

Most of the Japanese-Americans confined at Minidoka were from Seattle and Bainbridge Island as well as Alaska, California, and Oregon. Many were housed in a temporary camp at the Puyallup Fairgrounds. They were then sent by train to the Minidoka Center. The Minidoka Relocation Center was on 33,000 acres of unused federal land in Jerome County, in south-central Idaho located on the north bank of the North Side Canal providing water diverted from the Snake River to vast irrigation tracts. When the first incarcerees arrived at the Minidoka Center August 10, 1942, Morrison-Knudsen had not finished construction of the camp; there was no running water and the sewage system had not been installed. The initial reaction to Minidoka's stark and arid landscape by many of the incarcerees was one of discouragement. Upon arriving, one incarceree wrote: "When we first arrived here we almost cried, and thought that this is the land God had forgotten. The vast expanse of nothing but sagebrush and dust, a landscape so alien to our eyes, and a desolate, woe-begone feeling of being so far removed from home and fireside bogged us down mentally, as well as physically." Another evacuee wrote, "We were simply and utterly disgusted with... the camp... we found no running hot water, no sewer system, a hot, dry, dusty climate. For how long would we have to endure these conditions?"

The Center's administrative and residential facilities were situated on approximately 950 acres. Minidoka functioned as a self-sustaining community that had two elementary schools, a high school(that when it opened in November 1942 had an enrollment of 1,225), a library, a 196-bed hospital, fire stations, a warehouse area consisting of 22 buildings, a newspaper, bands, choirs, orchestras and sports teams. The barracks area at Minidoka was over three miles in length and one mile wide and contained 36 residential blocks. Each residential block included 12 tar paper barracks buildings; each with 6 small one-room apartments, one dining hall, one laundry building containing communal showers and toilets, and a recreation hall. Living conditions were harsh and the quarters cramped; "There were six apartments which housed 20 people. There was a family of 9 in a one-room apartment, size 20ft x 20ft... there were 16 families of 8 or 9 persons living in those one room apartments. Blankets suspended from the ceiling served as partitions ..." (Arthur Kleinkopf, Relocation Center Diary). Each apartment came furnished with Army issue cots and a pot-bellied stove for burning coal and sagebrush. Any additional furnishings often consisted of furniture that evacuees made from scrap lumber. Coal and water had to be hand carried.

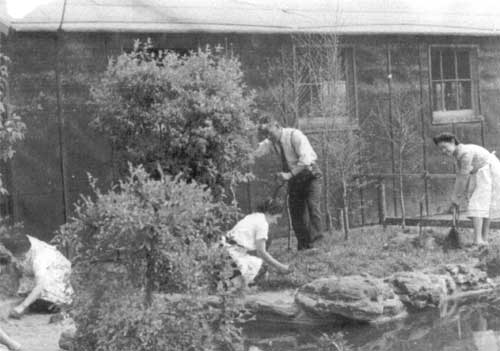

The climate could be extreme; from a low of -21(winter of '42) to a scorching 104 (July '42). In the spring and autumn months, incarcerees had to wade through ankle deep mud and contend with blinding dust storms. During the winter months, over 100 tons of coal a day were needed to heat the buildings. The residents were resourceful in their efforts to beautify the camp. Trees, flowers, and shrubs were planted throughout the camp as well as extensive gardens that provided the incarcerees with much of their fresh produce.

Population

The Center's population peaked at 9397, making the concentration camp Idaho's 8th largest city. 60% of Minidoka's Japanese Americans were Nisei, U.S. born and citizens by birth, the remaining 40% were Issei, born in Japan and not eligible at that time to become naturalized citizens no matter how long they had been living in America. In June 1943, 188 seniors, representing 52 different Oregon and Washington schools graduated from the high school. The Japanese Americans confined at Minidoka were an indispensable labor source for southern Idaho's agricultural-based economy. 2,400 Minidoka residents worked in agriculture during the 1943 harvest.

Despite the confinement experience, most Japanese-Americans overcame the initial feelings of loss and despair and remained intensely loyal to the United States. In 1943, the U.S. Army formed a segregated all-Japanese-American combat unit, the legendary 100th/442nd Regimental Combat Team which fought in Italy and France, becoming the most decorated unit of its size in American military history. Of the ten WRA confinement sites, Minidoka had the greatest numbers of volunteers join the 442nd, giving the Seattle Japanese-American community one of the highest WWII service records of any nationality/ethnic group in the nation. Approximately 1000 incarcerees from Minidoka enlisted in the military and 73 soldiers whose families were confined at Minidoka died fighting for their country. The families, because they were incarcerated, could not attend the funerals.

Camp Closing

In January 1945, the War Department began allowing incarcerees to return to the West Coast. The Minidoka Center officially closed on October 23, 1945. After the camp was decommissioned, the Bureau of Reclamation offered the land for homesteading to veterans. Farmhouses and irrigated fields now occupy much of the former site of southern Idaho's WWII concentration camp.

The relocation camp experience was a severe test of the character and loyalty of the Japanese-Americans. For those interned, life in the camps was a bitter experience but, in the long run, served to promote widespread acculturation and acceptance into the mainstream of American society. In 1952, the McCarran-Walter Act nullified racial restrictions in the Naturalization Law, which opened the U.S. to Japanese immigration, and allowed for the first time resident Japanese aliens to apply for citizenship.

For decades, all that visibly remained of the Minidoka War Relocation Center was the lone lava rock chimney tower and portions of a building wall, a solemn reminder of a complex and significant chapter in American history. On January 17, 2001, a presidential proclamation established the 72-acre Minidoka Internment National Monument in order to preserve and protect the legacy of this unique and irreplaceable historical resource. Since 2001, Friends of Minidoka has supported the National Park Service in its mission to preserve the site, now known as Minidoka National Historic Site, and educate the public to ensure a similar experience will not happen again.

Terms

Nikkei: persons of Japanese ancestry

Issei: First generation Japanese immigrants to America. Federal law prevented them from becoming naturalized citizens until 1952.

Nisei: Second generation, born in the U.S. and citizens by birth.

References

Takaki, Ronald. 1998 Strangers From a Different Shore: A History of Asian Americans. Back Bay Books, Little, Brown and Co. New York.

Sims, Robert C. 1978 "The Japanese American Experience in Idaho". Idaho Yesterdays, Spring 1978:2-10.